By Katelyn Tye-Skowronski

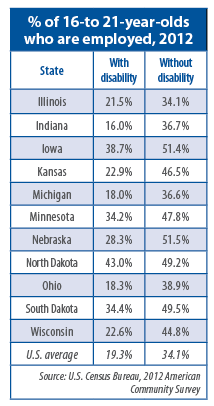

A year after they have left high school, 58 percent of Wisconsin students with disabilities report that they have not yet worked, participated in a job-training program or taken a postsecondary course. Rep. Robert Brooks, a first-year legislator in the state Assembly, believes the state and its schools can do better for this population.

His plan, introduced at least initially as a budget resolution, calls for new pay-for- performance incentives for school districts to improve their career- and college-readiness programs for students with disabilities.

Districts would be rewarded with a $1,000 payment for each student with an Individualized Education Plan who graduates and, the following year, is either employed or enrolled in a postsecondary school. (School districts and the state already collect this data.)

Schools would use these payments to expand their programs — for example, providing students with transportation to jobs, paying for specialized staff training, or developing college-prep courses for students with disabilities.

“The initiative was something [disability rights groups] already had on the table,” Brooks says. “I decided to get going on it.”

If the plan isn’t adopted with the budget, Brooks plans to then introduce it as a stand-alone bill in the fall. The Department of Public Instruction estimates the program would need $5.8 million in its initial year.

Brooks says his new approach complements existing state programs, including Gov. Scott Walker’s Better Bottom Line plan, which seeks to improve the job market for people with disabilities. Wisconsin is also home to the Let’s Get to Work initiative, a federally funded project overseen by the state’s Board for People with Developmental Disabilities. The program aims to improve employment outcomes for students with disabilities as they transition out of high school.

Each of the project’s 12 pilot schools has developed and implemented recommendations to improve services and outcomes. One strategy, for example, has been to provide access to courses that relate to the students’ interests and career goals.

In the project’s first year, the number of students with disabilities who had paid jobs tripled. After three years, more than 60 percent of the students from these pilot schools were working.

Stateline Midwest May 2015