By Laura Tomaka

For nearly 40 years, South Dakota Rep. Fred Romkema has run a jobs training center for a segment of his state’s population that he says is too often forgotten. About 140 people with disabilities are currently served at the Northern Hills Training Center, and 108 of them are earning a regular paycheck.

“With the right supervision and training and supports, they can succeed in employment in the community,” Romkema says about his experience working with people with developmental disabilities.

And that job success, he adds, is good not only for the individual, but the community — and the state — where he or she lives.

“There is potential there that we are not tapping,” Romkema says of the state’s population with disabilities. “There is a cadre of potential employees who can certainly contribute in some of the jobs that are difficult to fill.”

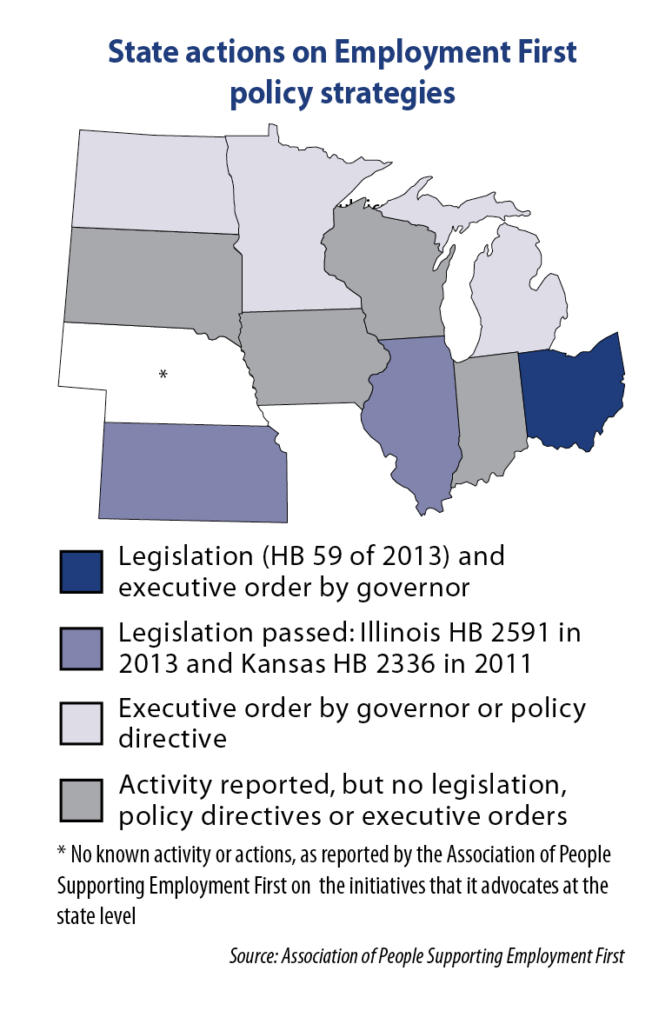

Through a mix of legislation and actions taken by governors, new initiatives are being launched in states across the Midwest to remove workforce barriers and to help get more disabled individuals into the workforce.

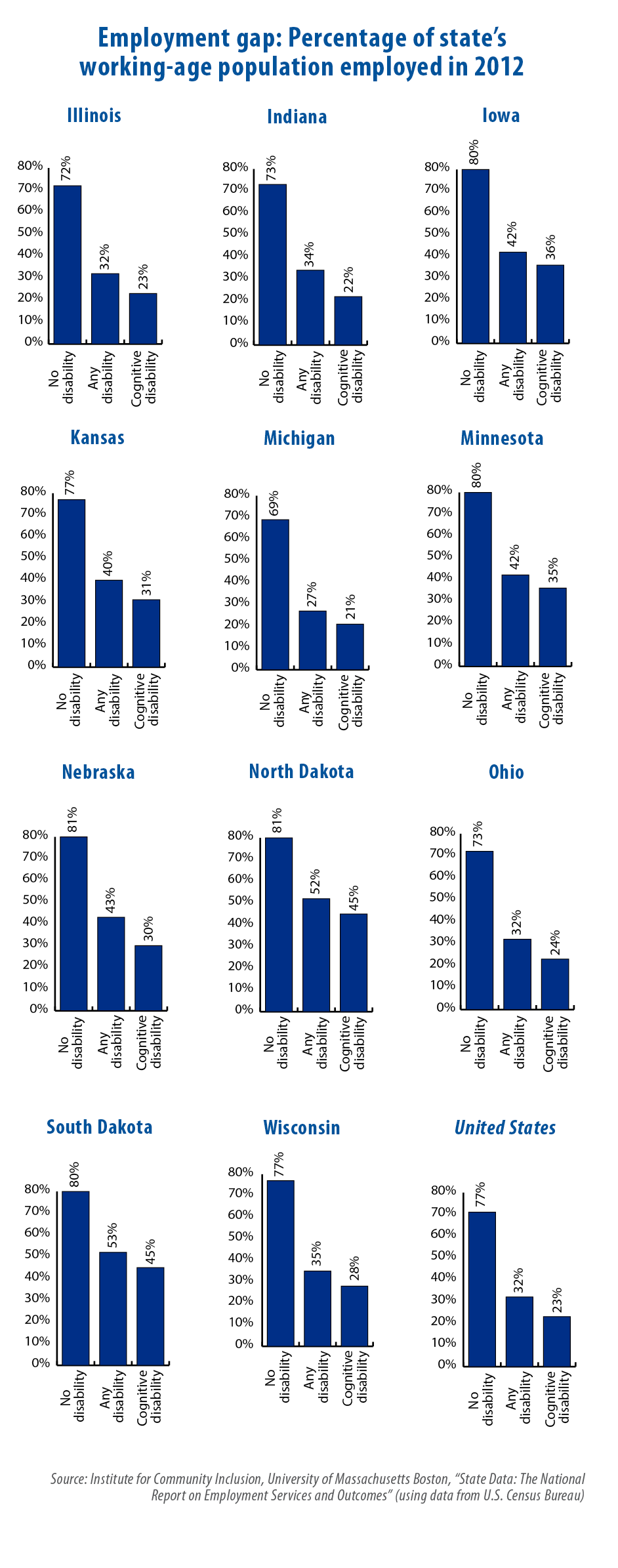

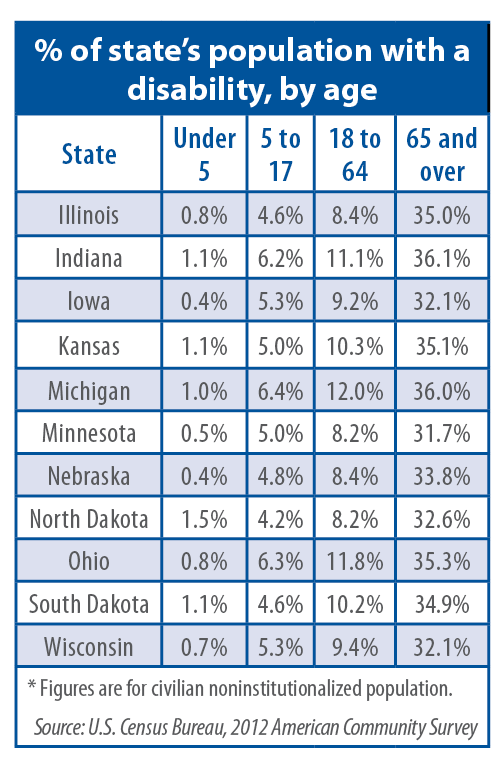

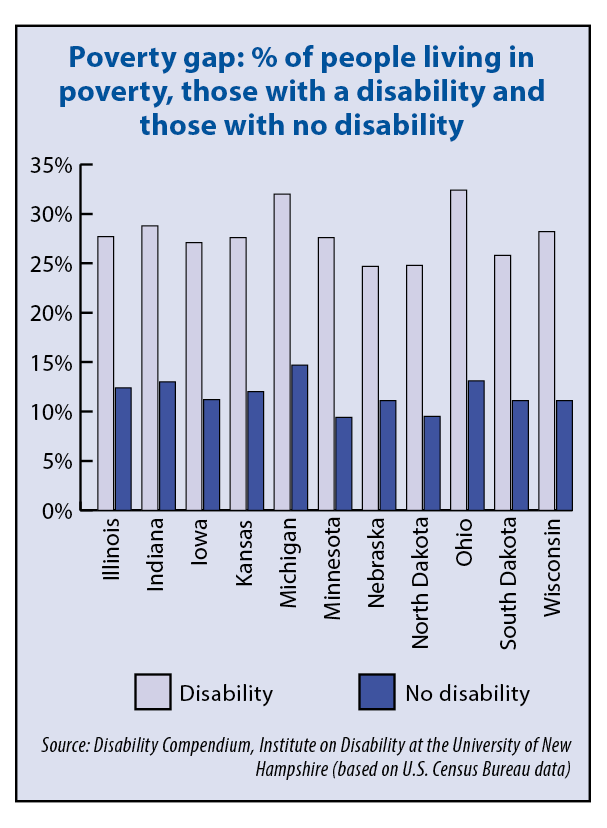

If successful, these initiatives could help close the large disparity in employment between the disabled and non-disabled. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate for those with disabilities was 13.2 percent in 2013, almost double the rate for those without a disability (7.1 percent). People with disabilities are also disproportionately affected by poverty — nearly 30 percent live in poverty, compared to less than 14 percent of people without disabilities.

“The employment challenge comes from the long-standing belief that people with disabilities have very limited abilities to work,” says Ryley Newport, a public policy associate with the Association of People Supporting Employment First, an advocacy group working for the full inclusion of people with disabilities in the community and workplace.

“People with disabilities [traditionally] have not been expected to work.”

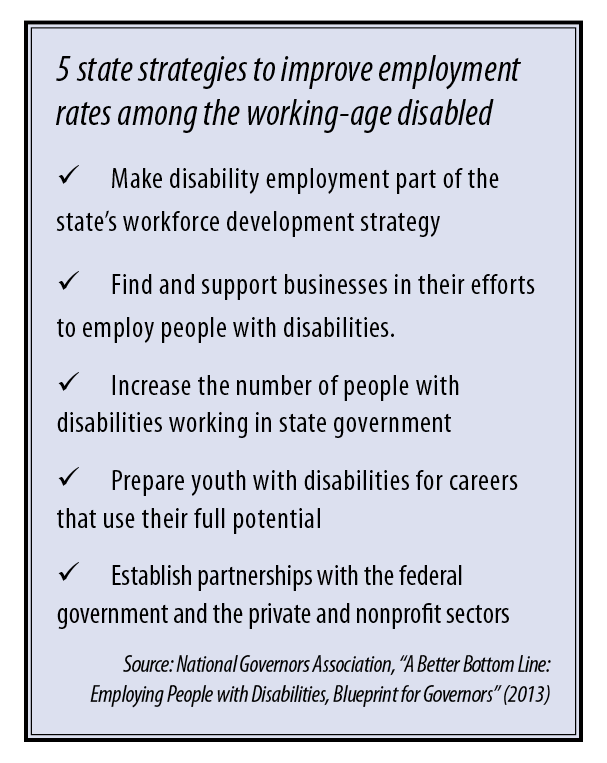

His association and other groups want to shift presumptions away from segregation, dependency and care and toward inclusion, employability and self-determination. And central to that strategy is changing policies at the state level, through an approach known as Employment First.

Employment First is based on a presumption that people with disabilities can be employed, and that the jobs for them should be in integrated, community-based workplaces for competitive pay. This approach also makes employment the first and preferred service option for working-age people with disabilities who rely on publicly funded programs and supports.

The goal of Employment First is to increase the quality of life for people with disabilities while also reducing reliance on traditional government supports. (Public support for unemployed workers with disabilities has been estimated to be $300 billion a year.)

“What we are trying to do is change it so everyone has opportunities to work and to be part of the mainstream,” Newport says.

According to Newport, Ohio is ahead of many other states in making this goal a reality. Gov. John Kasich launched his state’s Employment First policy, via executive order, in 2012. Legislation (HB 59) was then passed that same year. That original policy stated that “employment services for people with developmental disabilities shall be directed at community employment.”

Additional legislation in 2013 clarified that community employment means competitive employment in an integrated setting, and that all people with developmental disabilities are to be presumed capable of community employment.

Newport singles out two important provisions of Ohio’s current plan to employ more people with disabilities: First, it emphasizes the expectation of employability, and second, it sets objectives for increasing workforce participation.

Gov. Kasich’s goal was to increase integrated employment for people with disabilities by 10 percent (about 7,770 adults) by the end of fiscal year 2014. According to the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities, as of December 2013, the rate had increased by 8.5 percent.

For Ohio and other states trying new ways to improve employment outcomes, Newport says, tracking success, or the lack of it, is critical.

“There have been some states that have issued exemplary policies that have best practices embedded in them,” he says, “but we’ve seen no changes in the employment of people with disabilities.”

“We need to be able look at where we are in the states and what really is effecting [positive] change.”

In support of the state’s Employment First strategy, the Ohio General Assembly has appropriated $3 million a year in the current budget. Lawmakers have also done more to ensure the state’s young people are being prepared for work after school. For example, the individualized education plan, or IEP, for special-education students age 14 and older must now include a post-secondary goal of community-based employment.

Plans in Illinois, Michigan seek to maximize job opportunities

Though considered a model state, Ohio is far from alone in focusing more on the employment needs of individuals with disabilities. Illinois lawmakers passed the Employment First Act (HB 2591) in July 2013, and the state is now in the early stages of setting new policies and goals around it. The act, in part, requires state agencies to work together to make competitive employment for people with disabilities a priority.

“[It] will go a long way toward aligning state policy with Illinois’ values of inclusion and fair play for people with disabilities,” says Illinois Sen. Daniel Biss, the primary Senate sponsor of the bill.

Under the legislation, an Illinois task force will collect data from all state agencies and monitor how well state services are meeting the goal of community-based employment for people with disabilities.

“There’s so much loose talk around the goal of [integrated employment], but we’re at a loss of how to do something about it,” Biss says. “The Employment First Act is a necessary part of making sure our laws maximize the opportunities people with disabilities have to live with dignity.”

In Iowa, no formal Employment First laws have been passed and no policy directives are in place. However, it is currently a “protégé state” under a U.S. Department of Labor initiative designed to help states learn from one another on how to prioritize integrated employment.

Iowa has been matched with the state of Washington — designated as a “mentor state” because it already has effective policies and funding mechanisms in place. The program gives Iowa officials the chance to study, and possibly adopt, Washington’s Employment First strategies.

Michigan calls its new strategic plan for improving employment outcomes for the disabled “Better Off Working.” Released this year, it is the result of a collaboration among heads of state agencies, business leaders and advocates for the disabled.

The strategy mirrors some of the goals of Employment First. For example, de-emphasize disability as a de facto public assistance program, and instead refocus state services and programs on the goal of employment.

“Whatever the goals and aspirations and the hopes of people with development differences, it is our job to help them achieve those goals and not predetermine what their outcome is going to be,” says Lt. Gov. Brian Calley, the father of a child with autism and one of many people who helped shape the plan.

He adds that this change cannot occur with changes in policy alone; it also requires a shift in attitudes. And it also entails input, cooperation and buy-in from the business community.

To that end, the state this year began recognizing exemplary employers with Better Off Working Awards. Meijer, the Grand Rapids-based grocery and superstore chain, was one of two businesses to receive the inaugural award.

“They made the decision to employ people who have been largely locked out of employment opportunities in the past,” Calley says of the two award winners.

In turn, Meijer executives credit the state of Michigan, led by Gov. Rick Snyder, with raising awareness about the issue.

“[Gov. Snyder] really challenged businesses to come together with government and community organizations to say, ‘How can we create an environment for businesses to really engage in this work?’” says Rick Keyes, Meijer’s executive vice president of supply chain and manufacturing.

Meijer has a long history of hiring people with disabilities in its stores. However, Keyes says, the company has redoubled its efforts in recent years, in part spurred by the governor’s focus on the issue.

At one of Meijer’s production and manufacturing facilities in Lansing, for example, more than 30 percent of the employees are individuals with disabilities. The company worked with a community partner to help hire and train these workers, and also to provide the necessary accommodations and support.

“We used that success as a springboard for our other operations,” Keyes says, adding that increased hiring of individuals with disabilities “has had an amazing impact on our culture and on our team.”

Businesses such as Meijer wanting to hire individuals with disabilities may still need assistance from the state — for example, access to expertise and resources related to vocational rehabilitation. In turn, states need input from business leaders to make Employment First strategies succeed.

“The more you can speak with employers who have had a successful experience,” Newport says, “that is what will change the public’s perspectives on what people with disabilities can do.”

And Newport also says policymakers need to understand the perspective of the disabled workers themselves.

“Learn what it’s like for people with disabilities to work and know what it looks like to work in the community,” he says.

In South Dakota, Employment Works Initiative helps guide policymakers

South Dakota is led by a governor who witnessed first-hand the challenges faced by people with disabilities, including job-related struggles. Raised by deaf parents on a farm in southeast South Dakota, Dennis Daugaard has now taken on a very public role in advancing employment opportunities for people with disabilities.

In 2013, he launched the state’s Employment Works Initiative.

“This is one of the most promising new efforts … that I have seen over the years,” says Rep. Romkema, who served on a 35-member task force that was established as part of Employment Works and that has since released a series of recommendations for state action.

Those recommendations focus on ways the state can better connect businesses with the disabled population, provide more support for employers and employees, and promote awareness about the abilities and capabilities of many disabled people. South Dakota has since established a single point of contact, a business liaison, within the Department of Human Services to work with businesses on hiring people with disabilities.

Another task force recommendation was to eliminate disincentives for people with disabilities to find employment. Romkema views that policy area as being particularly important. Are there state or federal benefits that, in one way or another, discourage people from finding work?

South Dakota lawmakers found one in their own state and recently did away with it.

“If you earned more than $400, your benefits were reduced,” Romkema says, explaining a cost-share requirement in one of the state’s Medicaid waiver programs. “People realized there was no incentive to work.”

Leading by example: Hiring more disabled people in state government

Another way for a state to boost employment among disabled workers is to do the hiring itself.

In Minnesota and Michigan, for example, the governors have recently issued executive orders to improve their state governments’ hiring of individuals with disabilities.

Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton has directed state agencies to increase the employment of people with disabilities to 7 percent by 2018. Last year, 3.2 percent of the state’s government workforce was disabled. Dayton has expressed concern that the proportion of disabled people working for the state has dropped in recent years and that Minnesota has fallen behind the rest of the nation.

In Michigan, Lt. Gov. Calley now expects state agencies to set hiring goals and to establish aggressive new recruitment and retention plans that bring more people with disabilities into the state workforce.

“I’d like our state to be a magnet for this talent that is out there — this untapped potential,” Calley says. “And then I intend to show how good the performance is when you make these types of opportunities available.”

“This needs to be fully integrated, competitive employment,” he adds, “where somebody comes in with the same type of benefits and pay that anyone else would.”

Boosting employment for the disabled, Calley says, is part of an even greater objective that all states can play a part in achieving.

“So far I haven’t seen any government anywhere in our nation that has made enough progress yet in this constant fight against stigma,” Calley says. “This is an area where we all have a lot of learning to do.”

Because of his own family’s experience with autism, Calley has seen a growing awareness, understanding and inclusiveness of people with autism, as well as a greater willingness for individuals and families living with this diagnosis to be more open and public.

“I want that for everyone else,” he says. “I want people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder or depression or other types of developmental disabilities to have that same type of freedom.”

Employment First: Many states adopting new strategy for disabled

In seeking to promote greater job opportunities for their population of disabled residents, many states have adopted a model known as “Employment First.” It is based on the expectation that people with disabilities can work in an integrated work environment (given the proper training, supports and accommodations) and should receive compensation on par with non-disabled co-workers.

For states, this means building policies around the idea that competitive, integrated, community-based employment is the first and preferred option for youths and adults with disabilities. An Employment First strategy includes:

• giving young people with a disability access to early work experiences and transition-planning services as part of their education;

• setting measurable goals to increase employment among the disabled population in jobs that pay a minimum wage or higher, with benefits, and then tracking progress toward these goals;

• making employment the first and preferred outcome in the provision of publicly funded services for working-age people with disabilities; and

• funding quality services and supports that focus on long-term employment success.

“In the last decade, we’ve seen a boost in Employment First activity in the states,” says Ryley Newport, a public policy associate with the Association of People Supporting Employment First. According to this association and the State Employment Leadership Network, 30 states have something akin to an official Employment First policy. Of those, 12 have passed legislation stating that integrated employment is the first and preferred outcome in the provision of public funding and services for working-age people with disabilities. The other 18 states have policy directives or executive orders in place.

An additional 17 other states have some Employment First activities underway. For example, North Dakota passed legislation creating the Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities. However, the state has not yet formalized Employment First or its guiding principles.

Newport offers the following advice to policymakers when exploring and developing Employment First or related policies: “Learn what it’s like for people with disabilities to work. This connection and awareness not only helps when making funding decisions, but also helps focus on outcomes when creating employment policy.”